BACK TO VIRTUAL FIELD TRIP PAGE

Units here: Nerangleigh-Fernvale Beds (Late Devonian/ Early Carboniferous), Tingalpa Formation (Late Triassic), Woogaroo Subgroup (Late Triassic/ Early Jurassic)

Guidance notes (things to be thinking about when you write your report)

This site is important because at least three of our important rock units come together at this site so it allows us to interpret some stratigraphy as well as identify the conditions under where the rocks were deposited/ formed. See specific advice for each site below.

Toohey forest overview

Site 1 Tingalpa Formation (Behind the shed)

Guidance notes (things to be thinking about when you write your report)

- Look for lithological characteristics that might help you to determine the environment of deposition

The Shed (Tingalpa Formation) Tour (click to access)

The Shed (Tingalpa Formation) Intro video

___________________________________________________________________________

Site 2 Nerangleigh Fernvale Beds (Quarry)

Guidance notes (things to be thinking about when you write your report)

- This is a hard rock to identify, even in the field. Think about what type of rock it might be and use the structures you observe to figure out what has happened to this rock after deposition.

- Although you cannot seem in the field them we know that these rocks are composed of radiolaria, which are tiny microfossils which are used to determine their age. Here is a useful reference for this. (if you are not able to download: Aitchison, J. C. (1988). Early Carboniferous Radiolaria from the Neranleigh-Fernvale beds near Brisbane. Queensland Government Mining Journal 89 240–241.)

The Quarry (Nerangleigh Fernvale Beds) Tour (click to access)

The Quarry (Nerangleigh Fernvale Beds) Intro video

___________________________________________________________________________

Site 3 (Lookout)

Guidance notes (things to be thinking about when you write your report)

- At this site you should navigate round to examine the contact between this rock unit and another one. What type of contact is it?

- Look carefully at the composition of the material that makes up this rock. There is stratigraphic information to be extracted from this too. With some thought you should be able to work out the relative timing of the rocks that are found at Toohey Forest. Keep in mind that you need to make a Stratigraphic column for this whole location.

- Use the panoramas to also look at the view from the top of Peggs Look out. There are many mountains in the distance that are useful for your report (see below).

The Lookout (Woogaroo Subgroup) Outcrop Tour (click to access)

The Lookout (Woogaroo Subgroup) Outcrop

The Lookout (Woogaroo Subgroup) Hand Sample 3D model

___________________________________________________________________________

Miocene volcanoes

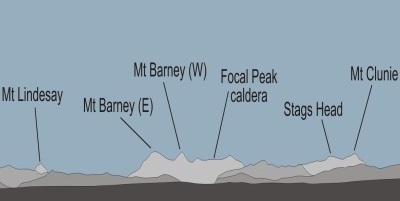

From this spot we can see much of SE Queenslands’ fiery past. If you follow the Pegg’s Lookout tour images you can see many mountains and low hills on the horizon. The majority of these are in fact volcanoes.

North of Brisbane are the Glasshouse Mountains (you can see these on the map on the VTF Home Page) which are around 26-27Ma. Mt Beerwah is the largest of the Glasshouse Mountains and is a volcanic plug made of Trachyte.

On the image above the majority of the peaks to the East (with the exception of Spring Mountain and White Rock), are associated with the Main Range Volcano (most active around 25 Ma). The area of the main central pipe of this volcano is unknown due to extensive erosion since the Miocene, but is likely to have occurred around the township of Kalbar. The mountain chain in the distance makes up the Great Dividing Range and is comprised mostly of basalts. Notable landmarks here include Cunninghams Gap where a major highway passes through opening up to the Darling Downs in the west, an area famous for its ‘Ice Age’ megafauna (we’ll look at these in our coming lectures and pracs). The peaks that are slightly closer, such as Mt Flinders, formed in the late stage of the Main Range Volcano when magma filled various vents and plugged them. The rocks today are mostly trachyte (intermediate in composition between andesite and rhyolite).

Just to the east, you can see the remains of the Focal Peak Volcano (most active around 24 Ma), centred on Focal Peak itself. The twin-peaked Mt Barney, just to the west, formed during the later stages of the Focal Peak Volcano. The rock here is a granophyre– it has the same geochemical composition as basalt and gabbro. Similar to gabbro, it is a plutonic rock, but cools slightly faster and therefore has crystal sizes that are intermediate between that and basalt. After it cooled, it was thrust upwards and today stands higher than the Focal Peak caldera.

You are going to “visit” the eastern margin of the Tweed Volcano (most active around 22 Ma) later in this virtual field trip, that was centred over Mt Warning. The northern flanks of the volcano are still largely intact and are similar to what they looked like back in the Miocene (although the volcano would have been much taller). They are represented here by the Lamington Plateau.

Calculating the movement of The Australian Plate

Each of these volcanoes formed as the Australian tectonic plate passed over a hotspot. Although it is estimated that the plate had been moving northwards as fast as 6-7 cm / year since it split from Antarctica, it slowed down considerably from 25-22 Ma, and briefly starting moving westward, when it collided the Ontong Java Plateau (an oceanic plateau that is part of the Pacific plate, northeast of New Guinea). After 22 Ma, it sped back up and started moving northwards again.

By taking into account the age and distance between the north/ south positions of the central pipes of the these volcanoes (Beerwah, Kalbar, Focal Peak, and the Tweed Volcano) you should be able to calculate the rate of plate speed before and during the collision in cm/year.

YOU SHOULD DO THIS LATER AND ADD TO YOUR REPORT.

Download the KMZ file here and measure the distances between the volcanoes using Google Earth.