Dinmore: A world-class fossil locality

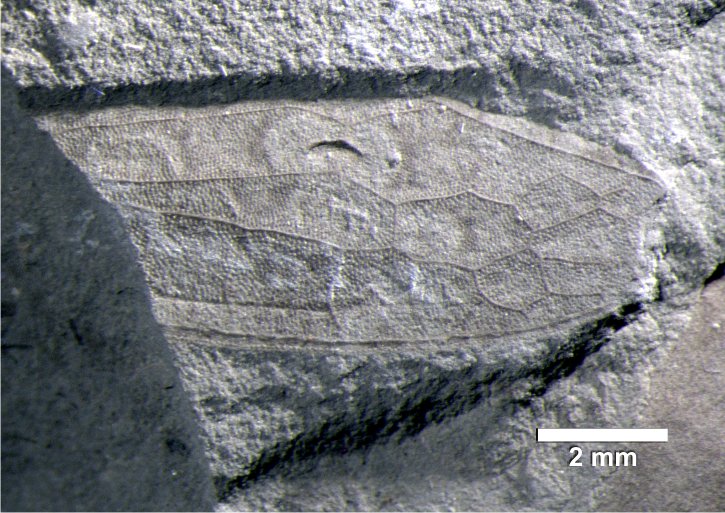

The Dinmore claypit is renowned as one of the world’s most productive and diverse plant fossil localities of its age. The deposits are incredibly rich in Dicroidium, a plant that had fern-like foliage but was unrelated to true spore-producing ferns. Instead, it produced seeds and pollen and was a more sophisticated, deciduous, tree-sized, woody plant. It is extremely variable in morphology and is one of the most biologically diverse plant groups of its time.

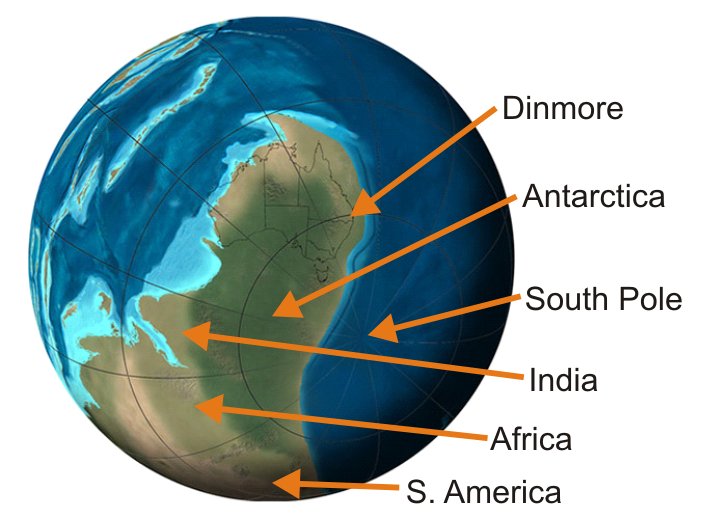

Dicroidium is an index fossil for a specific part of the Phanerozoic in Australia and is also widely distributed across all of the Gondwanan continents in rocks of the same age. Its distribution provides good evidence that these continents were united at that time. Other major plant groups represented in the Dinmore flora include conifers, ginkgos, bennettitaleans, cycads, pentoxylaleans (extinct group of seed-plants), peltasperms (another extinct seed-plant group), some additional seed-plants of uncertain affinity, and true ferns.

The Dinmore deposits have also yielded insect remains, freshwater bivalves and conchostraceans (bivalved freshwater crustaceans). In other parts of the rock formation, dinosaur footprints have even been discovered. It is very possible that we could uncover new dino records on our trip!

Fieldtrip objective 1: the fossils

Instead of the ERTH2002 teaching team providing specimens for pracs, we’re passing that responsibility to YOU! It will be the plant fossils that you collect on the fieldtrip that will form the focus of the follow-up prac class.

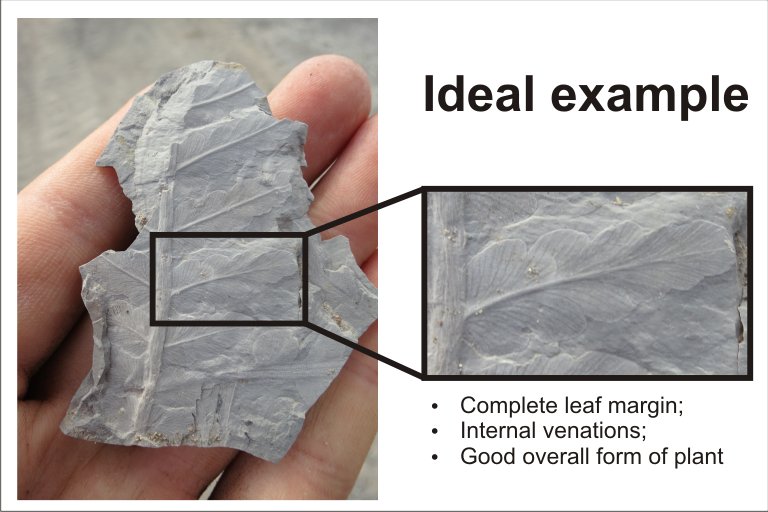

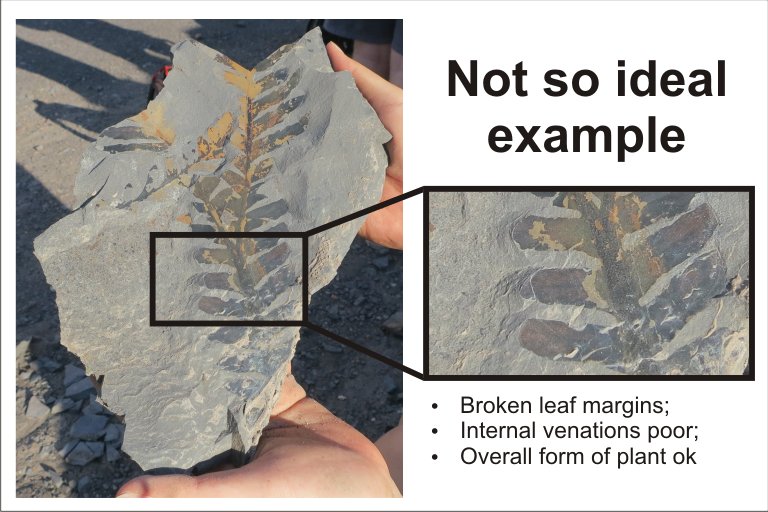

You don’t need to find the most complete fossil, but you do need to collect ones that are relatively well-preserved. For example, a leaf with complete external margins and internal structures such as venations would be ideal. Sometimes the most spectacular-looking plants aren’t necessarily the best for taxonomic identifications.

Fieldtrip objective 2: the rocks

The follow-up practical will involve taxonomically identifying your fossils (i.e., putting a name on to them). Taxonomy forms the basis for all studies palaeontological, from biostraigraphy to biochronology, and palaeobiology to palaeoecology. However, to understand the organisms, we need to first understand the rocks and the taphonomic signatures left behind.

Note taking in the field will be critical here. Look around the field area and make observations: What types of rocks do you see? How can you tell? What evidence is there of stratigraphy? How complete are the fossils? What are their styles of preservation? Do the fossils show evidence of abrasion?

Assessment

You’ll be provided with an exercise sheet that you’ll be required to fill-in. The exercise sheet, along with the follow-up practical will form the basis for the overall assessment for the Dinmore fieldtrip. Please see Blackboard for more details.

The follow-up in-class session will involve the identification of the fossils and a palaeobiological/ecological/environmental interpretation.

Can you keep the fossils that you collect?

In most cases, yes. However, fossils of organisms that are extremely rare or unusual will retained in the interests of Science. In previous years, some of the student-collected fossils have been donated to the Queensland Museum: our State’s official repository for natural and cultural history objects.

It might be a pain to have to give your fossil away, but it’s really actually a great honour. It means that you found something incredibly significant that tells the story of Australia. Not everyone gets to achieve that.

Where to meet

Please meet at the corner of Noel Street and Buckenham Street, Dinmore 4303. If you wish to drive there, there is ample parking in the area. For public trainsport, the nearest train station is Dinmore trainstation (around a 750 m work to the meet-up area). See your email / BB announcement for the time and date.

Things that you need to bring

Here are some critical items that you will need to bring with you:

Gear:

• Rock hammer *critical* (preferably with a chisel-end if you have one)

• Safety glasses (we can provide these)

• Gloves (optional, but recommended)

• Hand lense

• Notebook with pens and pencils

Protective gear / clothing:

• Sturdy boots (no thongs, pluggers, double pluggers, flip-flops, toesies, jandals, sandals, slippers or crocs! Your footwear must be closed-in: this is a requirement of UQ)

• It would be a good idea to bring a second pair of shoes for the ride home (the site gets extremely muddy after rain; a pair of pluggers would be ok in this case!)

• Long trousers (protect against spear grass and flying debris)

• Long sleeve shirt (protect against sun and spear grass)

• Hat

• Sunscreen

Other gear:

• Backpack

• Newspaper to wrap your fossils

• Minimum 1 L water

• Food (just in case you get hungry!)

*Please note that there are no toilets on site*